Elan Origins

The book Colin Chapman’s Lotus (1989; Robin Read, inputs by Mike Costin) provides an insiders’ glimpse of Chapman the person in the early years while taking Lotus from a private garage operation in 1948 to the founding of Lotus Cars in 1952, then through the fifties, the early single seat machines, the Elite saga, up to the early design work for the M2 project (Elan) in 1961. It describes the detailed groundwork from which the Elan (Lotus Type 26) blossomed.

Chapman realized that to afford his racing habit and to make himself rich at the same time, his company would have to be successful in building commercial sports and touring cars. Lotus’ first attempt at such a car was the Lotus Type 14, called the Elite (conceived in 1955, prototyped in 1957, manufactured 1959-1963). It utilized a monocoque, fiberglass-reinforced plastic (FRP) body rather than a chassis. Thus, suspension components and the engine were secured directly to the glass body. Many consider it to be one of the most beautiful cars ever, partially influenced by the Karmann-Ghia.

Type 14: Lotus Elite (image from an Autoweek article)

The Elite weighed less than 1200 lbs., utilizing a Coventry Climax FWE all-aluminum SOHC 1.2L engine providing 75 bhp in basic tune. Gas mileage was impressive. Performance was gratifying, due to its lightness and its inheritance of suspension bits and brakes from various competition models including the Type 11, 12, and 16. It was a successful racer, winning its class six times at Le Mans. But it retailed for $6,000, and more satisfying grand touring vehicles could be had for that price.

Although on a race track its limitations could be overlooked, its fragile nature, vibration and noise characteristics, and quality control issues caused it to compare poorly with the best efforts of the competition. Further, the manufacturing process for building a double-skinned FRP monocoque structure was sufficiently beyond current available techniques that the learning curve extended entirely through its production life.

The Elite was never commercially successful for Lotus. Deep suspicions of its impracticality of manufacture began to wash over Lotus Cars as early as 1959, when Ron Hickman began to write design notes about a new production car. The Austin-Healey Sprite revived the concept of a simple sports car based on readily available parts.

Chapman was doing double duty trying to keep Lotus Cars and Team Lotus above water. While he busied himself arranging for his racing engines to swap ends of the car, and at the same time planning for the production of his first sports coupe, he was forced to delegate design of the Type 17, the last front-engined Lotus racer. He specified MacPherson struts both front and back of the 17.

The front design as implemented was a disaster on the track and had to be scrapped. The fallout was that Chapman spent much of 1959 totally absorbed in salvaging the Lotus reputation from the Type 17’s problems. This in turn necessitated that he delegate initial design work on the next sports car on the drawing board entirely to Ron Hickman. It was to become the Type 26 Elan.

Initially, Hickman set out create the Lotus 26 as a replacement for the Lotus Seven, which had been an impractical (sunny days only) specialty car with minimal benefit to Lotus’ bottom line. All initial design for the Type 26 was based on a monocoque body shell with two doors and open top. Nobody had ever built one. In spite of the Elite problems, monocoque was still the preferred Lotus structural design, and perhaps lessons learned on the Elite would help make a better car. But as the Elite disaster continued to unfold, by 1960 it was necessary for the Type 26 to become the replacement for the Elite. Only a big success for the Lotus 26 could save the company.

By mid-1960, Chapman began to make noises about a chassis for the Type 26 to reduce risk in this must-succeed venture. He also became enamored by the independent rear suspension of the Triumph Spitfire, although he wanted a better version for the Type 26. But it was still too early for final admission of defeat on the original design; Ron Hickman continued to try to prove a design for a monocoque FRP structure for an open Type 26.

As it got closer to the final scheduled testing dates with no breakthroughs in sight, the engine and suspension engineers went begging for a test platform. Chapman concurred and designed the backbone steel frame in a weekend. It subsequently was used for 50K miles of testing under a fake body shell. By November 1960, Hickman threw in the towel and suggested they keep the test frame as the basis for the Type 26 chassis. A volume cost estimate of 10£ each for the 75 lb. frame sold the idea. Any alternative would be much more costly.

Hickman continued his overall design efforts and got approval from Chapman for the pop-up headlamps, a functional gimmick that would distinguish the Type 26 from its competitors. Chapman thought the Type 26 should be called the Elite again, but Hickman preempted him by having a naming contest in which the only acceptable name was Elan.

The Type 26/36/45

The book, The Original 1962-1973 Lotus Elan: Essential Data and Guidance for Owners, Restorers and Competitors (1989; Paul Robinshaw and Christopher Ross), provides an enthusiasts’ compilation of details of the Elan production throughout its 11 year run. It is a valuable reference book. There is a later expanded version of the book that addresses the Elan+2 as well.

The book, LOTUS Twin-Cam Engine (1988; Miles Wilkins), provides expert knowledge of design, development, restoration, and maintenance data for the engines powering the original Lotus Elan.

Note: Unattributed line drawings below are from the Elan Workshop Manual and from the Lotus Master Parts List for the S1, S2, and Coupe.

The Lotus Elan was produced from 1962-1973. The Elan+2 (4-seat coupe on a longer wheelbase) was also produced from 1967-1975 in an attempt to lure young families into the fold. The rest of this article discusses the 2-seat model only.

During its production from 1962-1973, the Elan was grouped into four Types and several sub-Series:

* Type 26 roadster (optional detachable hard top): S1, S2, S2 S/E

* Type 26R (racing version, ultra light weight, 160hp)

* Type 36 coupé (fixed head, FHC): S3, S3 S/E, S4, S4 S/E, S4 Sprint

* Type 45 drophead coupé (DHC, permanently affixed soft top): S3, S3 S/E, S4, S4 S/E, S4 Sprint

In this nomenclature, the Series referred to various available trim and performance levels within a basic chassis Type. S/E stands for Special Equipment, providing more comfort and more performance for a ~50 lb. weight penalty. Sprint, introduced in Feb 1971, was an upgraded S/E package with big valve engine (126 bhp) and two-tone paint. In practice, cars are most often identified just by the series, with coupe or roadster appended. Thus my car is a S3 S/E roadster (DHC for purists).

Type 45: Elan S3 DHC (from Carpictures.com, sold for over $20K)

Because of its approachable cost and technical sophistication, the Elan went on to become Lotus’ first commercial success, reviving a company stretched thin to the limit by the more exotic and less commercially successful Elite, and enabling funding of the Lotus success in racing over the next 15 years. No one knows how many Elans were produced over its nearly 12 year run. Serial numbers appear not to have been sequential, partly perhaps to create the impression of greater than actual production. A best guess is ~9,000 Elans were built, including 26R models and cars sold as kits.

According to serial numbers, 22 1500cc Elans were produced before the S1 launched in May 1963 with the final 1600 (1558cc) designation and serial number 26/0023. The change from S1 to S2 in November 1964 began at 26/3901, although it is not possible to account for 3900 S1 cars having been produced; a jump in sequence is suspected. The earliest S2 cars were hard to distinguish from the S1 except for interior changes (the wood dashboard went full width and a lockable glovebox was available); about 200 vehicles into production, new integrated (clustered) taillights appeared and minor component changes are noted, including improved brakes.

The later S2 cars already presaged some S3 changes, including the new clustered taillights and the addition of an S/E configuration. The change from the roadster-only S2 to the S3 series involved significant body modifications. The S3 series came either as the Type 36 coupé (introduced in August, 1965, at vehicle number 4510), or as the Type 45 roadster (drophead coupé or DHC, first introduced in June 1966 at vehicle number 5701). The S3 interiors were quite different, with electric windows and permanent window frames. The S/E configuration of the S3 included inertial reel safety belts and deluxe carpeting. The S/E engine had the hotter “C” cam (see the S3 S/E specs above for full details).

Model changes in the later years involved emissions and safety equipment upgrades to remain compatible with the US market. All cars up until the mid-S4 production came with dual Weber 40DCOExx carburetors, first 18, then 31. Later, for emissions control, Stromberg and Dellorto carbs were mounted. Beginning in 1970, different versions were marketed for three markets: internal UK, export, and Federal (US), as distinguished by the suffix letter on the vehicle number.

As Elan models (Series) advanced, it was hard to tell what components a specific Elan would come with. Sometimes old stock was used up in new models, and sometimes new stock was used to finish out an old model run. And sometimes major component change would occur in the middle of a model run.

Regarding my specific Elan configuration, the early S3 had toggle switches on the dash before switching to a different dash configuration with rocker switches in mid 1967, perhaps to conform to safety regulations in an important market segment. The early S/E models came with inertial reel safety belts as standard, initially from Teleflex. But these were only briefly installed before another likely regulation-conforming change took place.

At about the time of these transitions, the change-over from the Mk1 engine to the Mk2 also occurred (see drivetrain discussion below). Many vehicles may have ended up with a hybrid mix of engine components; using engine number as a clue, mine is some 300+ units before the official change-over to Mark II at engine number LP7800. Mine has a Mk1 block/crank, Mk2 con rods and oil pick-up pipe, hybrid Mk1/Mk2 sump, a Mk2 head, and Mk1 cam covers. Perhaps it was the hotter S/E configuration that warranted the early use of updated parts on pre-LP7800 engines such as this one; or more likely it was just luck of the draw from the parts bin.

So far as I can tell, Type 45 Elans with toggle switches on the dash numbered only in the low hundreds; cars with Teleflex inertial-reel safety belts many fewer yet. If I weren’t the original owner, I would think my car had a Frankenstein configuration of dubious origin. It was the Lotus way. Nothing was wasted; all stock needed to be converted to cash. No reference I’ve found has been able to get all these different variations correct. Robinshaw/Ross lays out a lot of information, but does not account for my engine having a Mk2 head, oil pickup, or 125E rods; they suggest such hybrids began some 300 units later.

Elan Chassis

The Elan’s FRP body mounts on a backbone frame pressed from mild, 18 gauge steel, with front and rear forks for accommodating front and rear suspension components and the engine. 16 mounting bolts hold the moulded, single-piece FRP body shell to the chassis. The frame was not rust-proofed and over time frequently rusts through around the front turrets. Most Elans have needed chassis replacement after being on the road for decades. These replacements are available from multiple suppliers, when one’s time arrives. Better, galvanized OEM Lotus frames are an option, as are re-engineered Spyder frames, with their added maintenance convenience.

Elan Drive Train

Elan chassis with complete drive train (from Robin Read’s book and Lotus sales literature)

The Elan engine is a 240 lb., bored-out, 1500cc Ford Cortina 116E cast iron block, upgraded with beefier Lotus cast iron crank and cast aluminum pistons, mated to a Cosworth cast aluminum DOHC hemi-head with chain-driven cams. The original in-block camshaft is utilized as a jackshaft to drive the fuel pump, oil pump, and distributor. The blocks initially were select grade Ford items, further classified by cylinder wall thickness into three Lotus grades. LAA or LA blocks were the most suitable for racing applications, where overboring would be desirable. Most were LB (retail)grade.

Except for the 22 earliest vehicles, the displacement was fixed at 1558 cc. Three engine variations can be identified, named here for reference convenience (see Miles Wilkins’ book for more discussion):

- Mk1: casting identifier 125E, to ~March 1967. Mk1 engines utilized 116E con rods, a crank with 4-bolt flywheel flange and rope seal, and a screw-in oil pickup tube. With the initial Mk1 heads, the tappets ran in unsleeved ports machined in the head. Later, in a head mod called Mk1.5, iron sleeves were inserted for the exhaust tappets. A 23 D-4 mechanical advance distributor was fitted.

- Mk2: casting identifier 2731E or “L”, to 1971. The Mk2 engines were purpose-built for Lotus because Ford no longer used that displacement block. The block grading system remained the same. With the Mk2 heads, a cast stiffening rib was added between #2 and #3 spark plug holes, and both intake and exhaust tappets ran in iron inserts. Other Mk2 engine changes were stronger 125E connecting rods, press-fit oil pickup tube, crank with 6-bolt flywheel flange and push-in lip seal. A 25 D-4 distributor with vacuum advance was fitted.

- Mk2+: casting identifier 701M “L”. Around the introduction of the Sprint, a new version of the Mk2 engine was fitted with beefier, square-shouldered steel main bearing caps.

Early and late engines were quickly identifiable by the location of the embossed LOTUS on the cam covers, appearing over each cam until October 1968. Subsequently, it appeared once over the timing case. But for current vehicles with later scavenged parts, this is not reliable, as the cam covers were interchangeable.

For the major Elan Weber engine variants, advertised states of tune are:

- Standard (blue cover “B” cam): 105 hp @ 6000 rpm, 108 ft-lb @ 4000 rpm, C.R. 9.5:1

- S/E (green cover “C” cam): 115 hp @ 6250 rpm, 108 ft-lb @ 5000 rpm, C.R. 9.5:1

- Super S/E, Big Valve (red or black cover “D” cam): 126 hp @ 6500 rpm, 113 ft-lb@5500 rpm, C.R. 10.3:1

Consult the Wilkins book for tuning details of later Stromberg and Dellorto engines destined for specific markets.

The power numbers were supposed to be net SAE output at the prop shaft. The initial advertised “B” cam power was later lowered to 95 hp at the introduction of the Sprint, which could then be advertised as a power increase of 25%. (This lower figure is quoted by Dave Bean Engineering; but Wilkins assures us that all 1558cc engines were good for at least 103 hp.) Later emission-controlled engines offered ~10% less power.

Anyone rebuilding a TC engine for the street might well opt for a big valve conversion and “D” cams, giving 130-135 hp and maintaining the streetable nature of the original. The upgrade adds a small percentage premium to the total cost: enlarging the inlet valve openings, upgrading the cams, and machining 0.040″ off the head. Pre-1967 engines should also be upgraded to the 125E rods. The Weber head is a rarity and great care should be taken with one. If money is no object, up to 150 hp can be obtained for a streetable car by extensive blue-printing and using custom cams. Any Mk1 engine can be upgraded to Mk2 features.

The Ford all-synchromesh transmission came in three gearing ratios: wide (1st=3.54), semi-close (1st=2.97), and close (1st=2.51; S1 option), mating with an 8″ single dry-plate clutch. Three final drive ratios were available: 3.55, 3.77, 3.90. Other gear ratios could be had via special order. A posting on http://www.lotuselan.net notes several transmission mods over the years:

The input shaft spigot bearing diameter changed from 17 to 15mm in 1967.

The front input oil seal also had 3 different sizes depending on year.

Three different types of mainshaft were used, up to 1966, 66 to late 70 and 71 on.

Two different types of synchro baulk ring were used.

The differential is a Ford gear set, housed in a Lotus-produced aluminum case, suspended from the rear of the backbone frame, connected by doubly-articulated half-shafts to the rear drive wheels.

The stock half-shaft joints are rubber “Rotoflex Metalastik” couplings from the Hillman Imp, rated to handle 140 ft/lbs torque, made somewhat beefier with the introduction of the Sprint. Racing donuts, with double the torque rating, are available for four times the price.

Perhaps the most desirable upgrade to an Elan, particularly an S/E model, is to replace the stock half-shafts with new ones utilizing CV joints instead of rubber donuts. It is a simple job, with complete replacement solutions costing $800-$1,400 and available from multiple suppliers. There is a small weight penalty, part of which will appear as unsprung weight.

Elan Suspension

Inspired by the Triumph Herald renowned for its tight turning circle, the Elan front suspension utilizes two unequal length wishbones and a strut consisting of concentric spring and damper. A forged steel arm connects the slightly-modified Triumph rack and pinion steering gear to the vertical link. The Elan has a turning circle of 29.5 feet and the steering is 2.5 turns lock-to-lock. The front suspension incorporates an anti-roll bar.

The independent rear suspension design derives from the Elite and also Lotus racing applications such as the Type 12. It uses a combined rear hub and shock absorber assembly, located at the bottom by a single tubular wishbone as the lower hub-chassis link, while also connected to the chassis by the upper end of the damper rod. The drive shafts have no lateral hub locating function. This design is essentially a MacPherson strut used at the rear drive wheels; in such an application it is now called a Chapman strut. No rear anti-roll bar is needed.

Elan Wheels and Brakes

Wheels are 4.5Jx13 pressed steel. The originals are four bolt. Later with the S/E cars, similar wheels were supplied for a knock-on hub and had five drive pegs. For road use, the original 80 profile 145/13 tires are competent to fully support the road forces the Elan is capable of generating. A 155HRx13 tire was fitted on later S4 models. For a while beginning in 1969, Lotus offered a low-profile tire option.

After-market 165/70×13 tires can be mounted on the stock rims, perhaps providing some added braking traction and a different aesthetic. Some mild relief on the rear lower spring mounts might be required. Elans involved in club racing were sometimes fitted with wider rims from the aftermarket, such as the Panasport Minilite mag wheel.

The 4 wheel outboard disc brakes are Girling with 9.5″ front and 10″ rear discs. There were only minor variations in caliper design over the Elan production beginning with the S2 cars. The original design was for inboard rear discs as with the Elite, to save unsprung weight. But this design could not be reconciled with the planned mechanical handbrake combined with the use of flexible driveshaft couplings.

Beginning with the S/E cars, a dual-circuit master cylinder with servo vacuum-assist was fitted. According to Road & Track, the stock brake/tire combination generates 0.87g of deceleration, a good but not great number (the contemporary and considerably heavier Datsun 2000 was measured at 0.90g). This comparison continues to mystify me; perhaps the light weight of the Elan limits its braking effectiveness if correct tire pressures are not observed.

Interior and Electricals

The Elan is a classic British car; its stock electrical system is positive earth (+vE). Since most modern electronic add-ons are negative ground, conversion to -vE is typically performed. On a stock Elan with no radio or other add-ons, this is straightforward, except for the tach. Simply reverse the battery and coil leads, then re-polarize the generator (disconnect field lead, briefly short field and earth terminals, reconnect field lead). The electric motors (starter/wipers/heater) are field-wound and are not sensitive to polarity. The electric tach is a special case. Either replace it with its negative ground twin, or remove the tach circuit from its case, unsolder the diode, and re-solder it in the opposite direction (instructions are available on the Internet). If the car is fitted with an aftermarket ammeter, its leads must be switched.

Popular electronic upgrades for the Elan, including alternators, electric fuel pumps, and electronic ignition systems are still available in +vE, so conversion is not necessary. But modern audio equipment, any external equipment that draws power from the cigar lighter, and any other installed equipment that is designed for -vE polarity, would need to be isolated and reverse-wired to work with +vE.

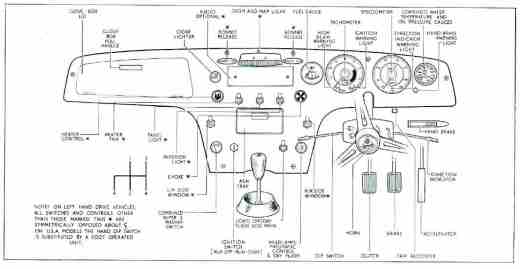

The dash controls are shown below. Beginning with the S3 or thereabouts, an ash tray was placed in the middle of the dash.

Early S3 S/E Elan Cockpit Layout With Toggle Switches (RHD)

Proceed to About This Elan.

Hi

I would like to know the chassis measurent since I’m restoring an S3 from a crash car.

Thanks a lot

Nice to hear from you Jorge. I added the chassis dimensions image to the post above.

I am searching for length of rear wishbone. The number on the image seems missing.

Do you know from what manual / book the images come from?

Thanks

Thanks for noting the error. I reposted the complete front and rear suspension diagrams, from the Lotus Elan Workshop Manual.

I loved my seven, and later my Elan. I wish I still had them.